Story first appeared in:

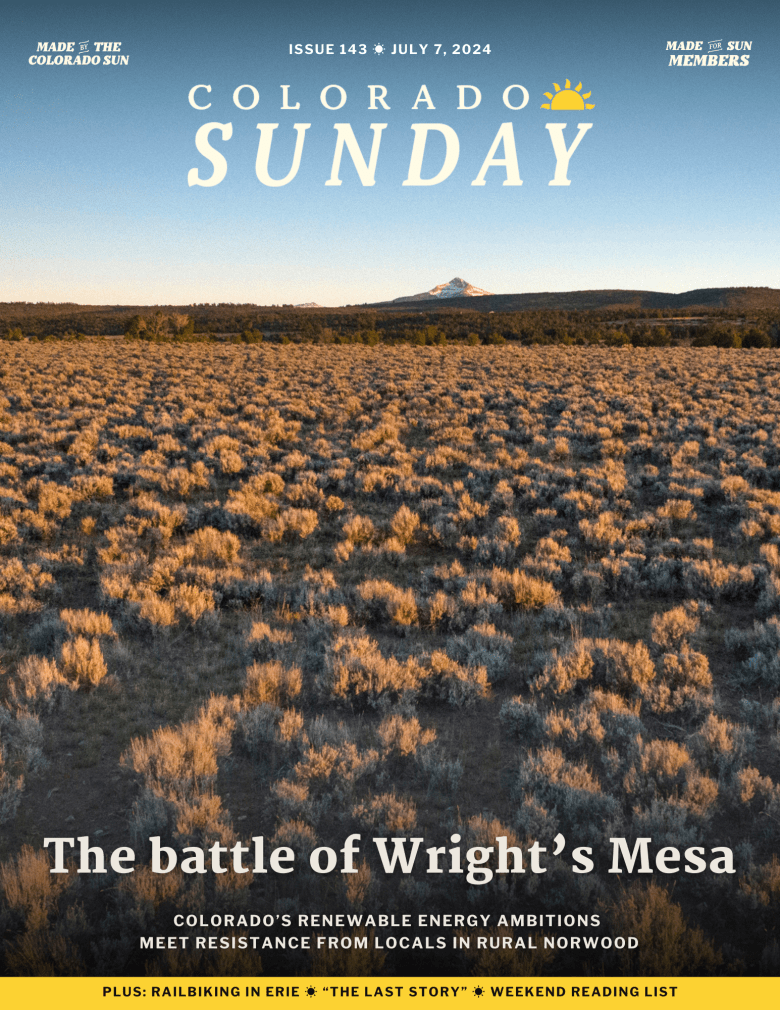

It seemed like a good idea. Put a large solar array on 640 acres of sagebrush and cedar about 30 miles northwest of Telluride. There was already a transmission line running through the property and only some cattle poking around in the shrubs and trees.

The Colorado State Land Board, owner of the parcel, had made siting renewable energy facilities a priority and even amended the lease on the Wright’s Mesa land to give solar panels precedence over cows. What could possibly go wrong?

And so, on a May evening last year, Seattle-based OneEnergy Renewables held a community meeting at the public library in Norwood, the mesa’s only town, to unveil a plan for thousands of solar panels and a 500 megawatt battery.

Norwood is home to about 550 people and all told there are about 2,000 folks living on the 30,000-acre mesa, so when more than 200 people packed the library and another 50 tuned in on Zoom, it was clear something was up.

The tenor of audience comments ranged from concerned to irate. “We’re not laughing. We’re pissed,” one resident said, according to a press report.

“They thought there would be support,” said Art Goodtimes, a former San Miguel County commissioner and 40-year resident of Wright’s Mesa. “I think they miscalculated.”

Thus began the Battle of Wright’s Mesa.

While it might appear this is yet another knee-jerk, not-in-my-backyard reflex, how the community — old-timers and new arrivals — came together and the questions they raised make Wright’s Mesa more than just another NIMBY tale.

On that May night, Vivian Russell, a Mesa resident who runs an afterschool program for San Miguel County teenagers, was at the library with a clipboard taking names and numbers as folks filed in.

“It was presented as a done deal,” Russell said. “It felt like a land grab.”

The Divide

The mesa, sitting at 7,000 feet, is land of juniper and pinyon pine, broad vistas and star-studded skies. In the morning, the sun rises over Colorado’s San Juan Mountains and in the evening, it sets behind the LaSalle Mountains in Utah.

At night the Milky Way hovers in the inky sky above, as Norwood is one of the world’s 38 certified Dark Sky International communities.

Dominating the plateau to the south is the 12,614-foot Lone Cone, an almost totemic presence for those on the mesa. A green apron of grass, aspen and oak wrap around the base and the mountain’s broad shoulders are draped with dark spruce forest from which a rocky, snow-coated summit rises.

“There is a saying among ranchers that if you are in the shadow of the Lone Cone, you’ll be all right,” said Scott Synder, a third-generation mesa rancher.

The Lone Cone provides all the mesa’s water, which for eons came down naturally through a small valley called the Divide. Thickly forested and rich in game, the Divide was a Ute hunting ground.

The first settler, Edwin Joseph, set up his homestead in 1886 near the Divide. (Joseph purchased the land for $100 from F.E. Wright who had staked the first land claim.)

The local yarn of the Yellow Bonnet Truce — and a yarn it seems to be — is that the Utes burned out Joseph twice. On the third try, Mrs. Joseph had returned from Grand Junction with a new yellow bonnet.

Chipeta, the wife of Chief Ouray, was so taken with the bonnet that in exchange for it the Utes agreed not to raze the Joseph homestead again.

The proposed OneEnergy solar project was not far from the Divide.

This story first appeared in

Colorado Sunday, a premium magazine newsletter for members.

Experience the best in Colorado news at a slower pace, with thoughtful articles, unique adventures and a reading list that’s a perfect fit for a Sunday morning.

“There have been some tensions.”

The names on the Russell’s clipboard turned into the Protect Wright’s Mesa Community Coalition, which tapped Mesa residents with expertise on subjects such as wildlife biology and fire safety to produce a 327-page impact statement.

Colorado is committed to building a lot of wind and solar generation. By one estimate solar generation must quintuple to help meet the state’s goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions from 2005 levels by 50% in 2030 and 90% by 2050.

While recognizing the value of clean energy, the mesa coalition raised the question of whether other values need to be sacrificed for it?

The fight over the solar project also begat a story of how the Old West and New West, which often grate on another, found common cause.

The traditional ranching community has been joined on the mesa by a new generation of “regenerative” and organic farmers as well as Telluride workers who can’t afford to live in Telluride.

“There have been some tensions,” said Goodtimes, who was Colorado’s first Green Party county commissioner and is the emcee and poet laureate of the Telluride Mushroom Festival. Back in the day, a mesa welcome for hippie arrivals, such as himself, he said, included a cowboy beatdown.

Today some families send their children to school in Telluride — a 45-minute commute — rather than have them attend Norwood’s dilapidated school. The school board voting to allow trained teachers to carry guns might have been another impetus.

But when it came to utility-scale solar, everyone united. Old West ranchers skeptical of solar joined forces with New West residents wary of an industrial-size operation in a rural area. “It was galvanizing here on the mesa,” Goodtimes said.

The question the mesa coalition posed is this: What is the balance between clean energy, agriculture, small town values, and preserving wildlife and those vistas that make Colorado, Colorado?

“It is up to the developers to show the Western Slope that it can be done.”

The questions the residents of Wright’s Mesa are asking are being raised across the Western Slope, which has some of the best solar radiance in the state and is becoming a prime destination for big solar projects.

Five Western Slope counties — Delta, Rio Blanco, Mesa, Montrose and San Miguel — imposed solar moratoriums while they worked on solar land use regulations.

“A lot of rural communities, especially those on the Western Slope, weren’t entirely prepared for how fast it’s going to happen,” said Adrienne Dorsey, vice president at the nonprofit COSSA Institute, which works with solar developers and communities.

The institute is a sister organization of the Colorado Solar and Storage Association, a trade group.

Moratoriums tend to follow the first proposal for a big solar project or even the hint of one, said Kate Doubleday, a researcher at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. “There’s been a chicken-and-egg aspect to it,” she said.

A NREL study found 39 of the state’s 64 counties had solar land-use regulations and 28 counties have some form of ground-based solar installations, which could range from a community-scale solar garden to a utility-scale installation.

On the Western Slope, the first big flap was in Delta County, where commissioners attempted to block a 100 MW solar project but couldn’t because they had no solar regulations. Moratoriums in Delta and neighboring Montrose County quickly followed.

Solar developers have turned up in La Plata, Montrose, Dolores, Montezuma and Garfield counties with a variety of customers and financing plans.

Tri-State bought a 110 MW solar installation developed in Dolores County, by JUWI Solar and the 80 MW Delta solar project being built by Guzman Energy is supplying power to the local cooperative, the Delta Montrose Electric Association.

In other cases, developers may build a project and bid to provide electricity to utilities seeking to buttress their portfolios.

Since the NREL study, Delta and Mesa counties have completed their new regulations and lifted their moratoriums. Montrose County will likely lift its solar freeze in the fall.

“We are ready to go if they come this way,” said Delta Commissioner Don Suppes. One big concern of western counties is the preservation of agricultural land and whether solar and farming can coexist. “It is up to the developers to show the Western Slope that it can be done,” Suppes said.

Colorado isn’t alone. The Sabin Center for Climate Law at Columbia University counted 395 local governments in 41 states with regulations on ground-based solar projects. The restrictions, the center said, “could have the effect of blocking a renewable energy project.”

This past legislative session, Senate Bill 212 passed with the aim of aiding and standardizing local solar codes. An early draft included language limiting local governments from blocking commercial solar on agricultural land.

That did not go over well with a host of local governments. “We beat that back,” Norwood Mayor Candy Meehan said. “They turned it into a study, so it could still come back.”

San Miguel County has a moratorium because of the fight on Wright’s Mesa and now it has a 49-page draft solar regulation, which would block large-scale solar on the mesa.

“It’s about managing where it goes,” said Anne Brown, a San Miguel County commissioner, who has been working on the regulations.

San Miguel and Ouray counties also have their own regional climate action plan seeking a 50% cut in greenhouse gas by 2030.

“We have very strong environmental values in our community and I know we want to participate in renewable energy development,” Brown said. “At the same time, we are not comfortable giving up our precious agricultural land.”

The state-owned land at issue is 560 acres that for the past 40 years has been leased to the Mex & Sons ranch for grazing and recreational hunting.

Neal Snyder started ranching on the Western Slope in the early 1900s and came to Norwood, where his son Raymond, nicknamed Mex, and his grandsons Monte and Scott continued the family’s ranching tradition.

The ranch is a cow-calf operation, with about 1,000 pairs, with the calves being sent on to feedlots before slaughter. The cattle summer up on the Lone Cone and other mountain pastures, while alfalfa for winter feed is grown in the fields around Norwood.

Come the fall, the cattle are brought down from the high country. The calves are shipped by truck and the cows journey down on a 30-mile, old-fashioned cattle drive with cowboys on horses and townsfolk riding along.

That’s how the Snyders have done it for more than a century.

The state parcel, on a road leading up to the Lone Cone, offers grazing for the Snyder bulls in the winter and a recreational hunting ground for deer and elk. The Farmer’s Water Company’s Gurley Ditch, the water supply for Norwood, runs through the middle of the property.

Snyder never heard a word from OneEnergy. The State Land Board staff informed the ranch the solar clause was being exercised and the land would be leased to OneEnergy.

OneEnergy’s plan was to combine the state tract with private land creating a nearly 1,000-acre site with 640 acres of solar panels.

“The State Land Board issued a three-year renewable energy planning lease to OneEnergy,” Kristin Kemp, a spokeswoman for the board, said in an email. “There is no update or change from the State Land Board’s perspective,” adding that the next steps are at the county level.

“I am not against solar,” Scott Snyder, 67, said. The ranch, he said, is in negotiations with a solar developer on some acreage it owns in the western part of the county, off the mesa. “Anyone who can make a little off their land should be able to do it.”

“It is just that this is right on our front door,” he said. “What if they put a big solar array in front of the Flatirons?”

Snyder said he was heartened by the broad community opposition to the project including support from his newest neighbors. “We are seeing some growth and new ideas coming in,” he said. “They’re not all bad.”

“The mesa has held true to its roots.”

Among the newcomers, at least by Snyder family standards, are Tony and Barclay Daranyi, who, 21 years ago, built a house, with hay bale insulation, and started the Indian Ridge Farm on 120 acres about 3 miles from the Snyders.

The Daranyis practice “regenerative agriculture,” which aims to enrich soils. At its peak, the farm raised organic grass-fed poultry, turkeys and hogs and a biointensive vegetable garden.

Tony Daranyi was a co-founder of Telluride’s newspaper the Daily Planet, and after selling his interest, he and Barclay set out on a new chapter seeing farming as a way to contribute to the community and the environment. Looking for land, they found their way to the mesa.

“Our guiding principle when we moved here was that we were not going to rock the boat,” Tony Daranyi said.

The farm has a 10 kilovolt, 52-panel solar array that provides all its electricity. The issue isn’t solar or no solar, but of scale. “Nine-hundred acres of an industrial solar project on our relatively small agricultural mesa was ridiculously too large,” he said.

In the years since the Daranyis arrived, some of the stores and restaurants in town have closed. “There are just fewer places to go,” Barclay Daranyi said.

It has, however, become a more diverse community. The most recent arrival: marijuana growers. Still, Tony Daranyi said, “the mesa has held true to its roots. It is an agricultural community.”

And both ranchers and new generation farmers were united when it came to the OneEnergy project. “We found a commonality with our neighbors in a love of place,” Tony Daranyi said.

The farm is also water rich with its own ponds, water rights and well rights and field irrigation. All vital on the mesa. “We have lots of sun, lots of good weather, not much water,” he said.

“This isn’t a done deal.”

Water is a major worry for John Bockrath, the Norwood Fire Protection District chief. When the department’s 17-person crew (including 14 volunteers) goes to battle a fire in the 845-square-mile district, it must bring its own water.

The department’s four-pump trucks can carry 5,450 gallons. “There is also a collapsible reservoir that can hold 2,000 gallons, if I can get it,” Bockrath said.

The department has no water of its own. “When there is a fire, ranchers come to fill the trucks,” said Bockrath, 62, who moved to Norwood after a long career with the Chicago Fire Department.

This is no small sacrifice. “There’s a saying among ranchers,” Mayor Meehan said, “you can take my wife but not my water.” OneEnergy’s estimate that it would need 5 acre-feet of water, or 1.7 million gallons, she said, was another strike against the project.

Mostly, the department battles naturally caused wildfires, but it brings its own water even when fighting a house fire in Norwood, with its aging water system. “If I hooked up to one of the fire hydrants, I’d blow a water main somewhere in town,” Bockrath said.

“Solar panels don’t burn, the lamination between solar cells could burn, but a bigger risk was the 500 MW battery,” he said.

Battery fires at solar installations are uncommon, but they do occur. In the past few years, there have been fires in Arizona, California and New York State.

“A small rural fire department like ours really doesn’t have the resources to fight an industrial fire,” Bockrath said.

The department’s one paid paramedic and emergency medical technician field about 400 calls a year, many from accidents on Norwood Hill, the steep, winding climb that is the only route to the mesa from the east.

The prospect of an estimated 300 workers commuting up and down Norwood Hill during project construction also raises the specter of more road accidents.

Bockrath put all these issues and concerns into one section of the coalition’s “cultural and ecological impact statement.”

In addition to Bockrath’s public safety section, there were chapters on potential environmental and wildlife impacts, and the possible effect on the mesa’s dark sky designation and impacts on adjacent farm fields.

In its presentation in May 2023, OneEnergy said stands of pinyon pine and juniper around the perimeter of the project and the Gurley Ditch would be excluded from the built area — creating a wildlife corridor.

The company also said it was “in conversations” with a local rancher to graze 200 sheep on the site. When Terri Snyder Lamers, whose family runs the biggest sheep ranch on the mesa, saw the scale of the solar project, she told OneEnergy they weren’t interested.

“There might be places it would work, but not in southwest Colorado with 15 inches of rain a year,” Lammers said. “We are too arid.”

The Farmer’s Water Co. included a letter in the impact statement opposing the project and adding that project “does not lend itself to agrivoltaics operations due to a lack of available water at the site.”

The upside of the project, as presented at the meeting, was $8.2 million in taxes to San Miguel County and $9 million lease payments that go to a state program for schools.

None of that money — or the electricity from the solar array — went directly to the mesa. The company was offering $50,000 in community donations.

“When it is all impacts and no improvements for the community, it makes people feel like we are a dumping ground,” Meehan said.

OneEnergy did not respond to a Sun request for comment.

The COSSA Institute’s Dorsey said “the Wright’s Mesa developers thought that they were doing their due diligence, contacting county authorities … inadvertently they didn’t engage the community.”

The institute is promoting early dialogue between developers and communities and asking developers to understand the needs a community may have and how they can help address them.

“With a goal of quintupling solar to meet the state’s climate goals, it’s going to take us all working together, ” Dorsey said.

If the San Miguel County solar regulations pass, a project the size of OneEnergy’s will not be permitted on the mesa, but the battle is not done, the mesa coalition’s Russell said.

The current draft would allow solar installations of up to 50 acres and that is still too large for Russell. The size of these “medium-scale” systems is one of the last points of contention, said Brown, the San Miguel County commissioner.

The planning commission’s final review is set for July 11. The coalition will be there as it has been for every planning and commission meeting. And then there is always the chance that way over on the other side of the Continental Divide, in Denver, the state will try to change the rules.

“There is still the threat of things going sideways,” Russell said. “This isn’t a done deal.”

So, the folks remain vigilant and united. “The Old West and New West are getting more nuanced,” Goodtimes said. “It’s not black and white, or red and blue.”

“We do need solar power and there may come a day when we run out of options and we need to put it here and we have to get used to looking at solar panels,” he said, “but this should be the last place to put them, not the first.”