A pair of geothermal energy developers are getting some much-needed funding to advance their quest to access the hot-water resource deep underground in Chaffee County. The money is coming from the state energy office and investors including one who “grew up around the benefits of geothermal” in Iceland.

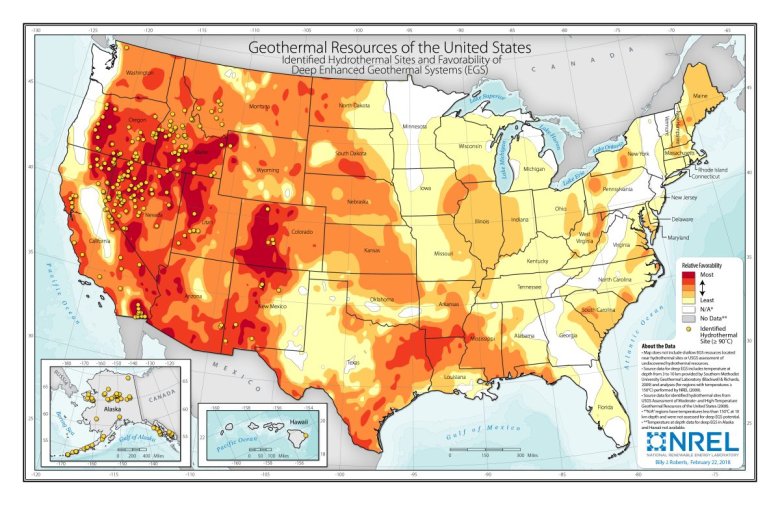

Hank Held and Fred Henderson, the pair behind Mt. Princeton Geothermal, have joined forces with Western Geothermal and Reykjavik Geothermal for exploration and development of the water that boils thousands of feet beneath the Earth’s surface along the Rio Grande Rift, which stretches from New Mexico into southern Colorado.

According to Held, Western Geothermal agreed to match a $500,000 grant Mt. Princeton Geothermal applied for from the Colorado Energy Office, which this year has awarded $7.7 million through the Geothermal Energy Grant Program to advance the use of geothermal technology in the state.

With the combined $1 million, Mt. Princeton Geothermal can move in the direction of drilling two exploratory wells they hope will tap a reservoir of water believed to sit at a depth of between 4,500 and 6,000 feet.

Held said the money will be “insufficient for our complete drill plan, so we are in consultation with additional prospective investors.”

But if the wells in question prove that a reservoir of hot water capable of generating 10 megawatts of energy lies beneath the land in Chaffee County, he said the partnership could yield a “potentially massive investment,” on the order of $40 million to $43 million.

Geothermal’s new rules

The Mt. Princeton merger preceded the Colorado Energy & Carbon Management Commission’s announcement Monday that it has adopted its first set of rules for deep geothermal operations. Those rules follow the expansion of the commission’s focus on energy and carbon management projects outside of oil and gas which went into effect last summer.

Held, Mt. Princeton’s CEO, said Tuesday he hadn’t had enough time to digest the new standards, but after “glancing over them” saw, “generally speaking,” they include revisions the men had the opportunity to comment on this spring.

In an interview earlier this summer, Held described some of the hoops he and Henderson have had to jump through since the ECMC took over.

☀️ READ MORE

“According to the previous procedure, we would make our geothermal drilling application to the Department of Water Resources,” he said. “Then, because our prospective well meets two criteria — it’s probably over 212 degrees and deeper than 4,000 feet — our application would be referred to the Oil and Gas Commission for their approval.”

The Oil and Gas Commission approved those types of wells in the past, but the issuing authority before the ECMC took over jurisdiction continued to be with the Department of Water Resources, he added. “Now, under ECMC, all of the regulations have changed, and they’re trying to separate our type of geothermal — hydrothermal — from enhanced geothermal, which involves fracking. With hydrothermal, we’re simply going down to what we believe to be a known hot water source to bump it up, extract the heat and put the water back in the ground.”

Henderson, Mt. Princeton’s chief scientist, has in the past said Colorado’s green energy regulations are some of the strictest in the country, making it hard for developers to attract investors.

But Gudmundur Heidarsson, one of Western Geothermal’s investors, said, “having lived in at least three European countries and three U.S. states, I can’t think of a government that’s more helpful than the Colorado government.

“I mean of course we’re doing something that hasn’t really been done in the state, so there’s a lot of learning,” he added. “There’s a lot of change in legislation and processes that needs to take place. But I’ve found officials to be easy to get hold of, to be helpful, and also, which I actually appreciate, a little bit careful in terms of making sure nobody’s coming in and doing something that is hard to reverse.”

Local resistance persists

For years, Henderson and Held have faced substantial pushback from residents of the Lost Creek Ranch subdivision, which lies about a mile from the proposed drill site. Opponents say 900 private wells could be impacted by a “geothermal project of this magnitude” and that their homes are built on the same fault line as the drill site, which they worry could “increase the potential for earthquakes.” They also fear noise pollution and odor a proposed plant could create.

But in closed-loop systems, which is likely what Henderson and Held would build, gases removed from the well are not exposed to the atmosphere and are injected back into the ground after giving up their heat. So air emissions are minimal, and Heidarsson says, “we have buildings all over the place, so that’s not going to be any different than any other industry, in a sense.”

Mt. Princeton Geothermal, Western Geothermal and Reykjavik Geothermal announced their merger June 19 at a community meeting in Buena Vista. Representatives from the Icelandic Ministry of Energy, Business Iceland, Green by Iceland and Chaffee County also attended.

Heidarsson said the meeting went well, which pleased him, because “you want to make sure you have a good communication with everybody around and you’re doing things in a sustainable way. As an entrepreneur in this area, I appreciate that, because it builds trust in the community and a path to continuing projects down the line.”

The Colorado Sun reached out to Tom McCracken, a vocal opponent of the plan, who declined to comment while he runs for Chaffee County commissioner, he said. Blane Clark, who McCracken suggested may speak with The Sun, didn’t return emails Thursday.

With new investors, new potential

Heidarsson said he and his partners discovered Henderson and Held after searching for a geothermal source in the Leadville area and failing to find one suitable for development.

“So, we kind of started to look down the (Rio Grande) Rift, if you will, and essentially came across what Hank and Fred had been doing for the last 12 or 13 years,” he added. “And since they had done some of the initial water testing and had some seismic data that they’d run in the site, we found that interesting and went to see if they were willing to work with us.”

They were, so Heidarsson brought some of his partners from Iceland as well as some research companies and the University of Reykjavik in to see where they could connect the dots on the project.

He said it’s a little late for them to start drilling this fall but he’s optimistic they can get the licensing, internal contracting and financing needed to have the preliminary drilling in place by early spring.

“But geothermal is one of those industries that just takes a bit of time to get everything right,” he added. “It’s not just turning on a spigot.”